Category: Accused, Brought to Trial, Convicted, Executed

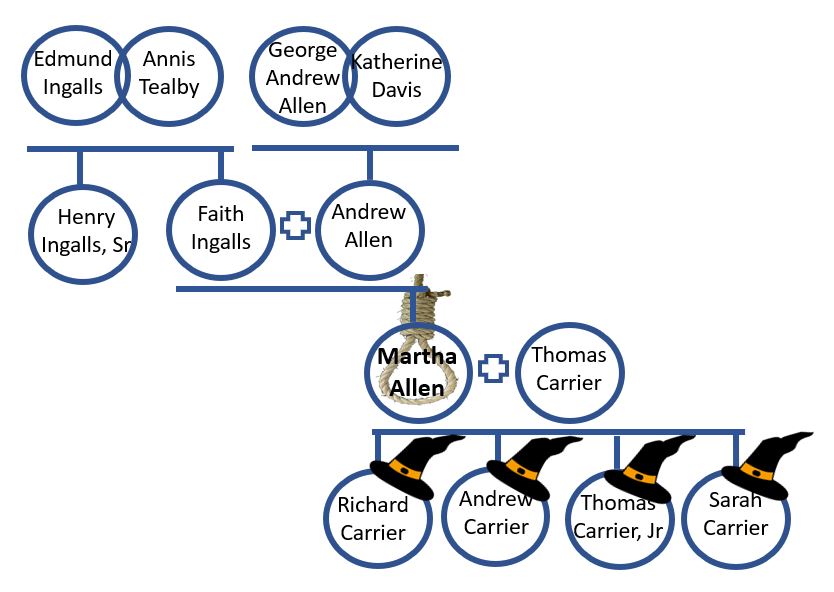

Ingalls Family Connection: Close family relationship: Faith Ingalls (Henry, Sr.’s sister)

Biographical Sketch of Martha Ingalls Allen Carrier from a Descendants’ Point of View

“August 5, 1692 five residents of Andover, Massachusetts were led to the gallows and, in front of a large crowd of witnesses, hung atop Gallows Hill in Salem for practicing witchcraft. The frenzy behind the Salem witch trials was based on the testimony of three young girls: Abigail Williams, Elizabeth Hubbard, and Susan Sheldon, and reinforced by townspeople who used the accused as scapegoats for their own misfortunes and to escape persecution. Four of the condemned were men, including John Proctor, the main character in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible.” The lone woman was an Andover housewife named Martha Carrier. It is Martha, my 8th great-grandmother, I’d like to honor today.

Hanson, D. (2010, September 23). Martha Allen Carrier. Retrieved from https://donna-hanson.blogspot.com/2010/09/martha-allen-carrier.html

She was born Martha Ingalls Allen in 1643 to Andrew Allen and Faith Ingalls, two of the original 23 settlers of Andover, Massachusetts. In 1674, she became pregnant with the child of an older Welsh servant, Thomas Carrier, who she married. The newlyweds relocated to Billerica. In 1676, they were blamed for a smallpox epidemic that claimed the lives of thirteen people including two of the Carrier children, Martha’s father and two brothers, her sister-in-law, and a nephew. A group of selectmen ordered the family to leave town immediately or pay a surety of 20 shillings per week if they wanted to stay. The Carriers were barred from entering public places. Although Martha, Thomas and the other children were afflicted with the disease, they survived. This was later was used as evidence of Martha’s “special powers.”

Thomas’ past is somewhat sketchy. According to Carrier family stories, Thomas’s exceptional physical size (he was said to be over 7 feet tall) strength, and fleetness of foot, led him to be chosen as one of the King of England’s Royal Guard. In 1649, when Charles I was put on trail and sentenced to death, it was Thomas who acted in the historic position as executioner. [Also, Thomas Morgan, alias Carrier, signed the execution orders for Charles I. His signature at that time was “Morgan” but sloppily written as “Worgan.” That was the name he used when he joined Oliver Cromwell’s Parliament army. He, according to sources on this, used the name Carrier to throw pursuers off when they followed Charles II ‘s command to find and execute all who played a role in the execution of his father, Charles I.] Unfortunately for Carrier, Charles’s son Charles II would re-take the throne and gain control the country. In May 1660, Charles II ordered the arrest of those responsible for his father’s death. Carrier adopted the surname “Morgan” and escaped to America around 1665. [The opposite is probably the case, as noted in the bracketed comment above.] It seems that Carrier lived an unsettled life at first, moving three or four times between Billerica and Andover. Although the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony did not approve of Charles I, they also did not approve of regicide. The facts behind Carrier’s actions may have found their way to the new colony and played a part in Martha’s undoing.

To make matters worse, Martha took charge of her father’s estate. [Martha Carrier probably had her name on the deed because she feared pursuers of her husband might find him through legal documents. This would have appeared to others as overstepping the bounds of a woman’‘s role] She immediately ran into friction with her neighbors, threatening vengeance upon those she believed were cheating her or her husband. She was described by Magistrate Cotton Mather as “a woman of a disposition not unlikely to make enemies; plain and outspoken in her speech, of remarkable strength of mind, a keen sense of justice, and a sharp tongue.”

In an excerpt from “Historical Sketches of Andover” the author notes that most of the accused confessed and thus averted the extreme penalty of death. Only Martha did not, at some time, make an admission or confession. “From the first moment to the last, under all the persuasions and exhortations of friends, under denunciations and threats of the magistrates and examiners, she held firm, denying all charges, and neither overborne in mind nor shaken in nerve, met death with heroic courage.” Martha’s three eldest children: Richard, Andrew, and Thomas were accused of witchcraft with their mother and tortured until they confessed. Their seven-year-old sister Sarah was not accused, but afraid and prompted by the interrogators, made to testify against her mother in court.

Several women accused confessed that Martha had led them to practice. Ann Foster said she rode on a stick with Martha to Salem Village, that the stick broke and that she saved herself by clinging around Martha’s neck. Her nephew, Allen Toothaker testified that he lost two of his livestock, attributing their deaths to Martha. Samuel Preston blamed the death of one of his cows on Martha stating that they’d had a disagreement and she’d placed a hex on the animal.

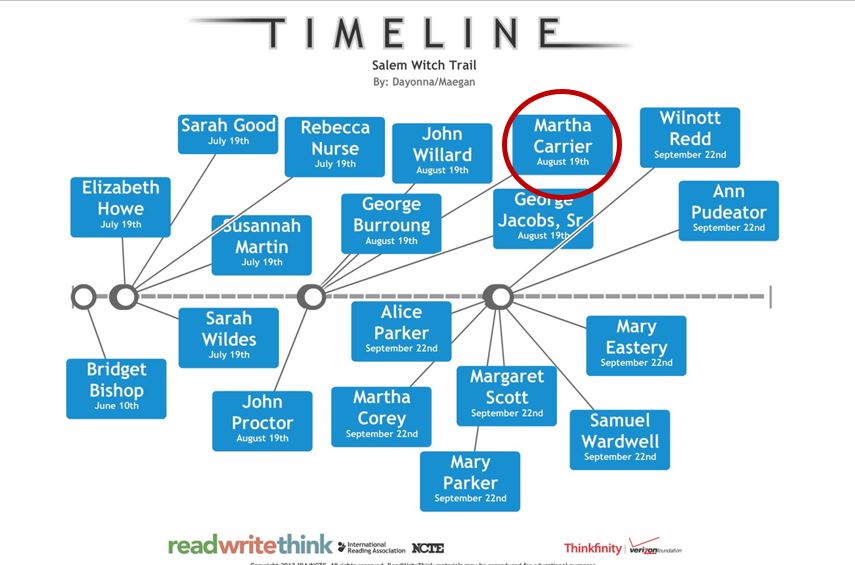

On August 19, 1692, Martha and four men were carried through the streets of Salem in a cart, the crowds thronging to see the sight. Even from the scaffold, Martha Carrier’s voice was heard asserting her innocence. Her body was dragged to a common grave between the rocks about two feet deep where she joined the bodies of Reverend Burroughs and John Willard.

On October 17, 1710, the Massachusetts General Court passed an act that “the several convictions, judgments, and attainders be, and hereby are, reversed, and declared to be null and void.” They ought to have extended the act to all who had suffered, rather confined its effect to those in reference to whom petitions had been presented. On the 17th of December 1711, Governor Dudley issued his warrant for the purpose of carrying out a vote of the General Assembly stating “by and with the advice and consent of Her Majesty’s Council, (to pay) the sum of 578 pounds to such persons as are living, and to those that legally represent them that are dead.” Martha Carrier’s family was awarded 7 pounds, 6 shillings.

On Tuesday, March 16, 1999, the Board of Selectmen from the town of Billerica, Massachusetts voted to rescind the banishment of the entire Carrier family as an “appropriate gesture” to the Carrier family. It was unanimously approved.

In October of 1995, I booked a two week’s vacation just south of Bar Harbor, Maine in a little fishing village overlooking an inlet. I’d hoped to visit all of the lighthouses along the coast and then rather play the rest of the vacation by ear. After the first week’s sampling of fresh fish and realizing that most of the lighthouses were off coast, decommissioned, or simply lighted totems and not reachable by car, I rambled south along the coast toward interstate 95 and home. It wasn’t a planned detour. Passing through Danvers, Massachusetts enroute to interstate 90, I noticed the signs for Salem. And took the exit.

Early in October, the town had already started preparing for Halloween celebrations. Banners flying from poles and windows accented by the golden red leaves painted a watercolor backdrop against the wrought iron fencing and granite stones in the memorial graveyard. Following the curve of the rough-carved letters with my fingers, I read “Martha Carrier, Hanged, August 19, 1692.” Grandmother.”

Biographical Sketch of Martha Ingalls Allen Carrier

“Martha Carrier (born Martha Allen; died August 19, 1692) was one of 19 people accused of witchcraft who were hanged during the 17th century Salem witch trials. Another person died of torture, and four died in prison, although the trials lasted only from spring to September of 1692. The trials began when a group of girls in Salem Village (now Danvers), Massachusetts, claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of being witches. As hysteria spread throughout colonial Massachusetts, a special court was convened in Salem to hear the cases.

Fast Facts: Martha Carrier

Known For: Conviction and execution as a witch

Born: Date unknown in Andover, Massachusetts

Died: Aug. 19, 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts

Spouse: Thomas Carrier

Children: Andrew Carrier, Richard Carrier, Sarah Carrier, Thomas Carrier Jr., possibly othersLewis, Jone Johnson. (2019, September 7). Biography of Martha Carrier, Accused Witch. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/martha-carrier-biography-3530322

Early Life

Carrier was born in Andover, Massachusetts, to parents who were among the original settlers there. She married Thomas Carrier, a Welsh indentured servant, in 1674, after giving birth to their first child, a scandal that wasn’t forgotten. [Other sources have Martha seven months pregnant at the time she married Thomas Carrier – still a scandal to be remembered] They had several children—sources give numbers ranging from four to eight—and lived for a time in Billerica, Massachusetts, moving back to Andover to live with her mother after her father’s death in 1690.

The Carriers were accused of bringing smallpox to Andover; two of their children had died of the disease in Billerica. That Carrier’s husband and two other children were ill with smallpox and survived was considered suspect—especially because Carrier’s two brothers had died of the disease, which put her in line to inherit her father’s property. She was known as a strong-minded, sharp-tongued woman, and she argued with her neighbors when she suspected them of trying to cheat her and her husband.

Witch Trials

Belief in the supernatural—specifically, in the devil’s ability to give humans the power to harm others through witchcraft in return for their loyalty to him—had emerged in Europe as early as the 14th century and was widespread in colonial New England. Coupled with the smallpox epidemic, the aftermath of a British-French war in the colonies, fears of attacks from nearby Native American tribes, and a rivalry between rural Salem Village and the more affluent Salem Town (now Salem), the witch hysteria had created suspicions among neighbors and a fear of outsiders. Salem Village and Salem Town were near Andover.

The first convicted witch, Bridget Bishop, was hanged that June. Carrier was arrested on May 28, along with her sister and brother-in-law, Mary and Roger Toothaker, their daughter Margaret (born 1683), and several others. They all were charged with witchcraft. Carrier, the first Andover resident caught up in the trials, was accused by the four “Salem girls,” as they were called, one of whom worked for a competitor of Toothaker.

Beginning the previous January, two young Salem Village girls had begun having fits that included violent contortions and uncontrolled screaming. A study published in Science magazine in 1976 said the fungus ergot, found in rye, wheat, and other cereals, can cause delusions, vomiting, and muscle spasms, and rye had become the staple crop in Salem Village due to problems with cultivating wheat. But a local doctor diagnosed bewitchment. Other young local girls soon began to exhibit symptoms similar to those of the Salem Village children.

On May 31, Judges John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney examined Carrier, John Alden, Wilmott Redd, Elizabeth How, and Phillip English. Carrier maintained her innocence, though the accusing girls—Susannah Sheldon, Mary Walcott, Elizabeth Hubbard, and Ann Putnam—demonstrated their supposed afflictions caused by Carrier’s “powers.” Other neighbors and relatives testified about curses. She pleaded not guilty and accused the girls of lying.

Carrier’s youngest children were coerced into testifying against their mother, and her sons Andrew (18) and Richard (15) were also accused, as was her daughter Sarah (7). Sarah confessed first, after which her son Thomas Jr. did as well. Then, under torture (their necks tied to their heels), Andrew and Richard also confessed, all implicating their mother. In July, Ann Foster, another woman accused in the trials, also implicated Martha Carrier, a pattern of the accused naming other people that was repeated again and again.

Found Guilty

On August 2, the court heard testimony against Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, and John and Elizabeth Proctor. On August 5, a trial jury found all six guilty of witchcraft and sentenced them to hang.

Carrier was 33 years old when she was hanged on Salem’s Gallows Hill on August 19, 1692, with Jacobs, Burroughs, Willard, and John Proctor. Elizabeth Proctor was spared and later freed. Carrier shouted her innocence from the scaffold, refusing to confess to “a falsehood so filthy” even though it would have helped her avoid hanging. Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister and author at the center of the witch trials, was an observer at the hanging, and in his diary he noted Carrier as a “rampant hag” and possible “Queen of Hell.”

Historians have theorized that Carrier was victimized because of a fight between two local ministers over disputed property or because of the selective smallpox effects in her family and community. Most agree, however, that her reputation as a “disagreeable” member of the community could have contributed.

Legacy

In addition to those who died, about 150 men, women, and children were accused. But by September 1692, the hysteria had begun to abate. Public opinion turned against the trials. The Massachusetts General Court eventually annulled verdicts against the accused witches and granted indemnities to their families. In 1711, Carrier’s family received 7 pounds and 6 shillings as recompense for her conviction. But bitterness lingered inside and outside the communities.

The vivid and painful legacy of the Salem witch trials has endured for centuries as a horrific example of false witness. Noted playwright Arthur Miller dramatized the events of 1692 in his 1953 Tony Award-winning play “The Crucible,” using the trials as an allegory for the anti-Communist “witch hunts” led by Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. Miller himself was caught up in McCarthy’s net, likely because of his play.

Sources

“Salem Witch Trials Timeline.” ThoughtCo.

“The Salem Witch Trials Victims: Who Were They?” HistoryofMassachusetts.org.

“Salem Witch Trials.” History.com.

“Salem Witchcraft Trials.” WomensHistoryBlog.com.

Bracketed information in the above two sketches are credited to

Carrier Notes from Carrier Family Website. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.carriergenealogy.com/Notes.html

Hite, R. (2018). In the Shadow of Salem: The Andover Witch Hunt of 1692.

Thomas Carrier from Binnuy’s Billerica. (2003). Retrieved from http://www.angelfire.com/band2/billtrivia/tcarrier.html

Primary Source on Carrier’s Examination, Indictments, Accusers

The best source is the Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project

“ SWP No. 024: Martha Carrier Executed, August 19, 1692 .” SWP No. 094: SWP No. 024: Martha Carrier Executed, August 19, 1692 – New Salem – Pelican, University of Virginia, 2018, salem.lib.virginia.edu/n24.html.

My grandmother was an Ingalls and a relative as well. My mother is doing family history and found a lot of information but we would love more if you have it. I’m not sure how I found this blog but I hope this message gets to you.

LikeLike

Hi Suzie, I am sorry it has taken me so long to respond. I haven’t been on the blog since my sisters and I made a trip to Lynn, Massachusetts (founded by our shared ancestors Edmund and Ann Ingalls), Andover, Massachusetts, and Salem to learn more about the family. I don’t know where you live, but the trip to these places is terrific for any descendant of Edmund & Ann. Our lineage is really exciting. My email is rose@ggrotta.com so feel free to contact me there.

LikeLike