Category: Accused, Indicted, Brought to Trial, Executed

Ingalls Family Connection: Extended relationship through marriage: Mary Osgood

Biographical Sketch of Mary Ayer Parker

“The Untold Story of Mary Ayer Parker: Gossip and Confusion in 1692”

Written by Jacqueline Kelly, copyright, 2005

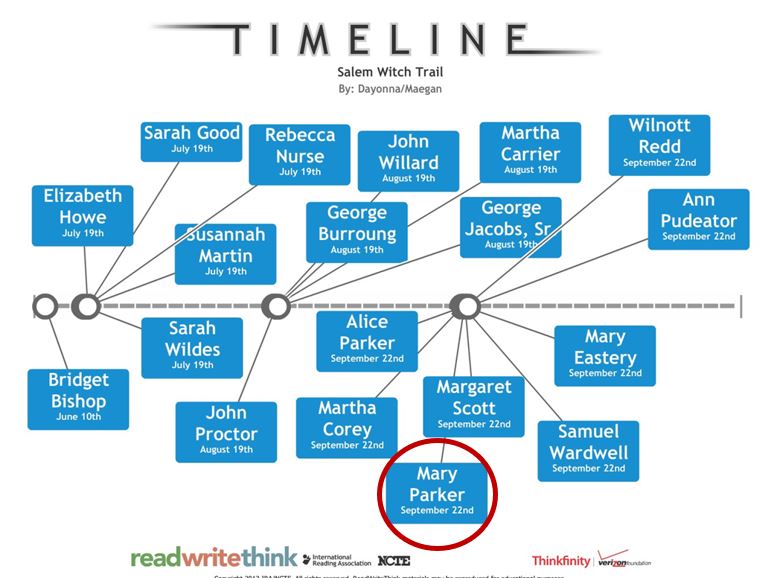

In September1692, Mary Ayer Parker of Andover came to trial in Salem Massachusetts, suspected of witchcraft. During her examination she was asked, “How long have ye been in the snare of the devil?” She responded, “I know nothing of it.” Many people confessed under the pressure of the court of Oyer and Terminer, but she asserted they had the wrong woman. “There is another woman of the same name in Andover,”1 she proclaimed. At the time, no one paid much attention. Mary Ayer Parker was convicted and hanged by the end of the month. Modern historians have let her claim fall to the wayside as well, but what if she told the truth? Was there another Mary Parker in Andover? Could it be possible that the wrong Mary Parker was executed? We know little about the Mary Parker of 1692. Other scholars presumed her case was unimportant-but perhaps that assumption was wrong.

The end of her story is recorded for every generation to see, but the identity of this woman remained shrouded in mystery for over three centuries. We still don’t know why she was accused in 1692. Puritan women were not particularly noteworthy to contemporary writers and record-keepers. They appeared occasionally in the court records as witnesses and plaintiffs but their roles were restricted to the house and family. Mary Parker was a typical Puritan wife. She appeared in the records only in birth notices and the records associated with the will of her late husband Nathan Parker. Notably, the records included no legal trouble at all, for witchcraft or anything else.

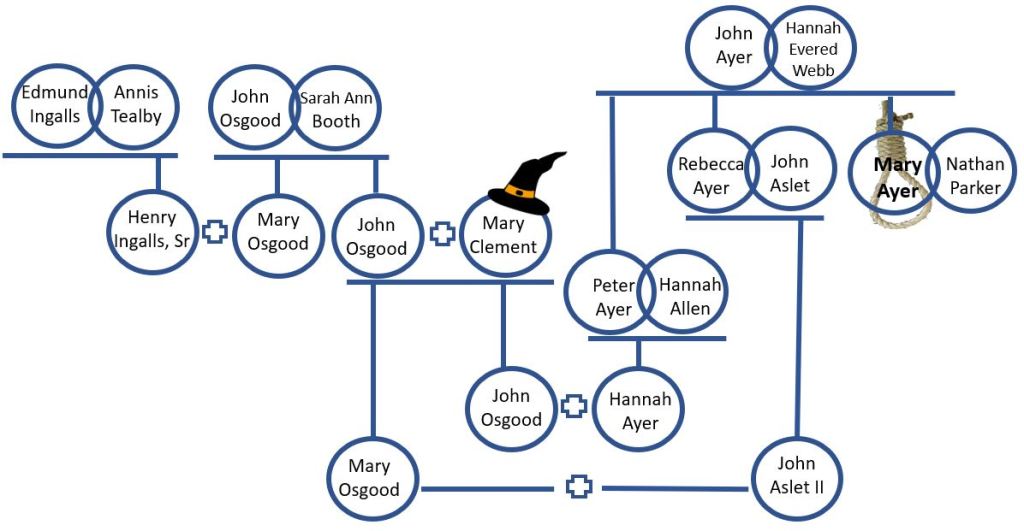

John and Hannah Ayer gave birth to their daughter Mary sometime in the early to mid 1600’s. Mary and her siblings may have been born in England, and later moved to North America with their parents. The Ayers moved several times during the early stages of their settlement in America but resettled for the last time in 1647 in Haverhill.2

The family was apparently of some prominence. Tax records from 1646 showed that John Ayer possessed at least one hundred and sixty pounds, making him one of the wealthiest settlers in Haverhill.

Mary Ayer married Nathan Parker sometime before her father’s death in 1657. Although no marriage record survived in the hometowns of either Nathan or Mary, the wording of her father John Ayer’s will made it obvious that she was married with children when it was written.3 Nathan married his first wife Susanna Short on November 20, 1648.4 Within the next three years, the couple relocated to Andover, where she soon after died on August 26, 1651.5 Andover’s Vital Records listed the birth of Nathan and Mary Parker’s first son John in 1653.6 Nathan could have remarried and had children within the two years after the death of his first wife.

Mary and Nathan marriage was not documented but we do know Nathan and his brother Joseph settled in Newbury, Massachusetts sometime in the early 1630’s. They settled in Andover where they were amongst its first settlers.7 Nathan came over from England as an indentured servant8, but eventually he became rather wealthy in Andover. The original size of his house lot was four acres but the Parker’s landholdings improved significantly over the years to 213.5 acres.9 His brother Joseph, a founding member of the Church, possessed even more land than his brother, increasing his wealth as a tanner.10 By 1660, there were forty household lots in Andover, and no more were created. The early settlers, including the Parkers, would be those of importance. By 1650, Nathan began serving as a constable in Andover.11 By the time he married Mary Ayer, his status was on the rise. It continued to do so during the early years of their marriage as he acquired more land.

Mary and Nathan continued to have children for over twenty years after the birth of John Parker in 1653. Mary bore four more sons: James in 1655, Robert in 1665, Peter in 1676, and a son Joseph.12 She and Nathan also had four daughters: Mary, born in 1660 (or 1657)13, Hannah in 1659, Elizabeth in 1663, and Sara in 1670. James died on June 29, 1677, killed in an Indian skirmish at Black Point.14 Robert died in 1688 at the age of 23. Hannah married John Tyler in 1682.15 Nathan and Mary’s daughter Elizabeth married John Farnum in 1684.

When Nathan died on June 25, 1685, he left an ample estate to his wife and children.16 Mary Ayer Parker brought an inventory of the estate to court in September of the same year, totaling 463 pounds and 4 shillings. The court awarded her one-third of the house and lands, equal shares to Robert, Joseph, Peter, Hannah, Elizabeth, and Sarah, and a double share to John.17 Mary Parker widow obtained an estate of over 154 pounds-a good amount of money in the late seventeenth century.

Mary Parker did not appear in Essex County records after September 29, 1685 when she brought the inventory to court. We know little about her interaction with her neighbors and the community after her husband’s death. The Parkers were a respectable family that continued to root itself in the community. So why, less than a decade after her husband’s death, was Mary accused as a witch? There was no documented friction with any of her neighbors, any no prior accusations. The closest tie Mary had with witchcraft was a distant cousin on her father’s side, William Ayers whose his wife Judith was accused of witchcraft in 1662.18 But this was not enough to justify Mary’s accusation. What really happened in 1692 to Mary Ayer Parker?

The Salem crisis had spread to Andover when William Barker Jr. named her in his confession on September 1, 1692.19 He testified that “goode Parker went w’th him last Night to Afflict Martha Sprague.” He elaborated that Goody Parker “rod upon a pole & was baptized at 5 Mile pond,” a common reference to a union made with the devil. The examination of Mary Parker occurred the next day. At the examination, afflicted girls from both Salem and Andover fell into fits when her name was spoken. The girls included Mary Warren, Sarah Churchill, Hannah Post, Sara Bridges, and Mercy Wardwell. The records state that when Mary came before the justices, the girls were cured of their fits by her touch-the satisfactory result of the commonly used “touch test,” signifying a witch’s guilt.20

When Mary denied being the witch they were after Martha Sprague, one of her accusers, quickly responded that is was for certain this Mary Parker, who had afflicted her. Sprague and Mary Lacy effectively fell into fits. Historian Mary Beth Norton discovered that Mary Parker was related to Sprague; she was Sprague’s step-great-aunt.21 Mary Parker’s son-in-law John Tyler’s father Moses Tyler had married Martha’s mother.22 Martha also lived in Andover, and the Tylers and the Parkers were friendly for sometime before their families were joined in marriage.23 Still, it was a distant relation and Martha was only sixteen years old at the time of the trial, so it is doubtful she knew Mary Parker personally.

Nevertheless, Mary Parker’s defense was ignored, both by the courtroom, and most historians until now. However, Mary Ayer Parker told the truth: there was another Mary Parker living in Andover. In fact there were not one, but three other Mary Parkers in Andover. One was Mary Ayer’s sister-in-law, Mary Stevens Parker, wife of Nathan’s brother Joseph. The second was Joseph and Mary’s daughter Mary. The third was the wife of Mary and Joseph’s son, Stephen. Mary Marstone Parker married Stephen in 1680.24 To complicate things even further, there was yet another Mary Parker living nearby in Salem Towne.

Confusion could easily have arisen from the multitude of Mary Parkers abound in Essex County. However, similarities between Mary Ayer Parker and her sister-in-law may have instigated confusion in even her accusers. The two Mary’s married the Parker brothers by the late 1640’s, and began having children in the early 1650’s. They had children of the same name including sons named Joseph and daughters Mary and Sara (Mary, daughter of Nathan and Mary may have died soon after her father 25). Nathan and Mary Parker’s son James, born in 1655, and Joseph and Mary Parker’s son John born in 1656, died on June 29, 1677, killed by the Indians at Black Point.26 In 1692, both Mary Parker Sr.’s were reasonably wealthy widows. Joseph’s wife received their house and ample land from his will, dated November 4, 1678.27 The two women shared almost fifty years of family ties. But in September of 1692, it was only Nathan Parker’s wife who was accused, tried, and found guilty of witchcraft. Why was Mary Ayer brought to trial?

On the surface, the two Mary Parkers seemed almost interchangeable but the will of Joseph Parker revealed something important about his branch of the Parker family. Joseph made some peculiar stipulations regarding the inheritance of his son Thomas. The will described Thomas as “who by god’s providence is disenabled for providing for himself or managing an estate if committed to him by reason of distemper of mind att certain seasons.”28 The management of his portion of the estate was given to his mother Mary until her death, after which, Thomas would choose his own guardian.

This “distemper of mind” seemed to run in the family. Stephen Parker later petitioned in September 1685 that his mother be barred from the management of her own affairs for the same reason. Stephen revealed that his mother was in a “distracted condition and not capable of improving any of her estate for her owne comfort.”29 Whether mental illness influenced the reputation of Joseph Parker’s wife cannot be ascertained, but it is likely that if she was mentally instable, it was well known in the tight-knit community of Andover.

Mental illness was often distrusted and feared. In fact, a case in 1692 involved a woman with a history of mental illness. Rebecca Fox Jacobs confessed to witchcraft in 1692 and her mother Rebecca Fox petitioned both the Court of Oyer and Terminer and Massachusetts Governor Phips for her release on the grounds of mental illness. According to her mother, it was well known that Rebecca Jacobs had long been a “Person Craz’d Distracted & Broken in mind.”30 Evidently mental illness could have made someone more vulnerable to witchcraft accusations. This does not guarantee the girls intended to accuse Mary Stevens Parker but it does make the case for Mary Ayer Parker’s misidentification stronger.

A notorious figure in Salem Towne, also named Mary Parker muddled the case further. This Mary Parker appeared multiple times in the Essex courts and made a reputation for herself beginning in 1670’s. In 1669, she was sentenced for fornication.31 In 1672, the court extended her indenture to Moses Gillman for bearing a child out of wedlock. A year later, she went back to court for child support from Teague Disco of Exiter.32 The court sentenced her ten stripes for fornication. She came to trial two more times for fornication in 1676 33. A scandalous figure indeed, Mary from Salem further sullied the name “Mary Parker.”

A disreputable name could have been enough to kill the wrong woman in 1692. In a society where the literate were the minority, the spoken word was the most damaging. Gossip, passed from household to household and from town to town through the ears and mouths of women, was the most prevalent source of information. The damaged reputation of one woman could be confused with another as tales of “Goode So-and-so” filtered though the community. The accused Sarah Bishop had a history of witchcraft suspicions, especially concerning the death of Christian Trask. Her death, ruled a suicide, remained a controversy and many believed that Sarah Bishop had bewitched her.34 The Court of Oyer and Terminer questioned Sarah on April 22, 1692, but the “Goode Bishop” business did not stop there. Susanna Sheldon, joining the cast of afflicted girls, claimed that she saw Bridget Bishop in an apparition who told her she killed three women, one of them being Christian Trask.35 Sarah and Bridget lived in different parts of Salem but Susanna wrongly attributed gossip about Sarah Bishop to Bridget Bishop simply because they shared a last name. The confusion associated with their cases proved how easily gossip could be attributed to the wrong woman. The bad reputations garnered by Mary Parker the fornicator from Salem, and the mentally ill Mary Stevens Parker of Andover could have affected the vulnerability of Mary Ayer Parker.

Mary Ayer Parker told the truth about the other Marys, but the court ignored her. William Barker Jr. came in to speak against her. He testified “looking upon Mary Parker said to her face that she was one of his company, And that the last night she afflicted Martha Sprague in company with him.”36 Barker Jr. pointed Mary out in court but he may have been confused himself. In his own confession, William accused a “goode Parker,” but of course, he did not specify which Goody Parker he meant.37 There was a good possibility that William Barker Jr. heard gossip about one Goody Parker or another and the magistrates of the court took it upon themselves to issue a warrant for the arrest of Mary Ayer Parker without making sure they had the right woman in custody.

Mary Parker’s luck plummeted when Mary Warren suffered a violent fit in which a pin ran through her hand and blood came from her mouth during her examination. Indictments followed for the torture and other evil acts against Sarah Phelps, Hanna Bigsbee, and Martha Sprague. Martha’s indictment was rejected, returned reading “ignoramus,”38 but the indictments for both Hannah Bigsbee and Sarah Phelps were returned “billa vera”, and the court held Mary Parker for trial. Sara claimed that Mary tortured her on the last day of August as well as “diverse other days and times.” Hannah said that Mary tortured her on the first day of September: the indictment stated that she had been “Tortured aflicted Consumed Pined Wasted and Tormented and also for Sundry othe[r] Acts of Witchcraft.”39

Capt. Thomas Chandler approved both indictments. Significantly both Sarah and Hanna were members of the Chandler family, one of the founding families in Andover. The Captain’s daughter Sarah Chandler married Samuel Phelps on May 29, 1682. Their daughter Sara Jr. testified against Mary Parker in 1692.40 Hannah Chandler, also the daughter of Capt. Thomas, married Daniel Bigsbee on December 2, 1974.41 Capt. Thomas Chandler’s daughter Hannah and granddaughter Sarah.gave evidence that held Mary for trial. Did the Chandler family have it out for the Parkers?

Thomas and his son William settled in Andover in the 1640s.42 Elinor Abbot wrote that they originally came from Hertford, England.43 The revelation of strong Chandler ties to Mary’s case is peculiar because until then, the relationship between the Parkers and the Chandlers seemed friendly. Public and private ties between William, Thomas, and the Parker brothers were manifest in the public records. Nathan and William Chandler held the responsibility of laying out the land lots, and probably shared other public duties as well.44 Joseph Parker’s will called Ensigne Thomas Chandler45 his “loving friend”, and made him overseer of his estate.46 Nathan Parker’s land bordered Thomas Chandler’s and there was no evidence of neighborly disputes.47 It is difficult to understand where the relationship went bad.

The only hint of any fallout between the families came more than a decade before Joseph Parker’s 1678 will. On June 6, 1662, Nathan Parker testified in an apprenticeship dispute between the Tylers and the Chandlers.48 The Chandler family may have felt Nathan Parker unfairly favored the Tyler family in the incident. Bad blood between the Chandler and Tyler families could have translated into problems between the Chandler and Parker families. This discord would have been worsened by the alliance between the Tyler and Parker families through Hannah Parker and John Tyler’s marriage in 1682.

This still does not seem enough to explain the Chandlers’ involvement 1692. Perhaps after Nathan Parker’s death in 1685, neighborly tensions arose between Mary’s inherited state and the bordering Chandler estate. The existing records betray nothing further. Perhaps these speculated neighborly problems were coupled with the desire to distract attention from an internal scandal in the Chandler family.

In 1690 Hannah and Daniel Bigsbee testified in the trial of Elizabeth Sessions, a single woman in Andover who claimed to be pregnant with the child of Hannah’s brother Joseph. The Bigsbees refuted her claim and insisted she carried the child of another man.49 The Chandlers were respected people in Andover; even Elizabeth referred to them as “great men,” and they surely resented the gossip. The crisis of 1692 was a perfect opportunity for them to divert attention away from the scandal. When Mary Parker was arrested, they found the ideal candidate to take advantage of: her husband and her brother-in-law were no longer around to defend her and her young sons could not counter the power of the Chandlers.

After the initial indictments, Hannah Bigsbee and Sarah Phelps dropped from documented involvement in the case. Here, the documentation gets rather sloppy and confused. Essex Institute archivists erroneously mixed much of the testimony from Alice Parker’s case in with Mary Parker’s. When the irrelevant material is extracted, there is very little left of the actual case.50

The only other testimony came from two teenage confessors: Mercy Wardwell and William Barker Jr. On September 16, fourteen-year-old Barker told the Grand Inquest that Mary “did in Company with him s’d Barker : afflict Martha Sprag by: witchcraft. the night before: s’d Barker Confessed: which was: the 1 of Sept’r 1692”.51 Eighteen-year-old Mercy did not name Mary a witch, but did say that “she had seen: the shape of Mary Parker: When she: s’d Wardwell: afflicted: Timo Swan: also: she: s’d she saw: s’d parkers Shape: when the s’d wardwell afflicted Martha Sprage”.52

Nothing else remains of Mary Parker case. It appeared that Mary’s trial was over on September 16, 1692. She was executed only six days later. Evidence seems lacking. In essence, Mary was convicted almost solely from the testimony from two teenage confessors. Her examination, indictment, and grand inquest all took place expediently, and within one month, Mary was accused, convicted and executed.

Her death seems irresponsible at the least, and even almost outrageous. She was convicted with such little evidence, and even that seems tainted and misconstrued. The Salem trials did her no justice, and her treatment was indicative of the chaos and ineffectualness that had over taken the Salem trials by the fall of 1692. However, her treatment by historians is even less excusable. The records of her case are disorganized and erroneous, but what has been written about the case is even more misinformed. Today it is impossible to exonerate the reputation of Mary Ayer Parker. The records that survive are too incomplete and confused. But perhaps we can acknowledge the possibility that amidst the fracas of 1692, a truly innocent woman died as the result of sharing the unfortunate name “Mary Parker.”

Kelly, Jacqueline. “The Untold Story of Mary Ayer Parker: Gossip and Confusion in 1692.” Salem Witch Trials, Cornell University, University of Virginia, 2018, salem.lib.virginia.edu/people/?group.num=all&mbio.num=mb42.

Yet Another Goody Parker!

Another woman with the name Parker was hanged on September 22, 1692. Her name was Alice Parker. She was the wife of a mariner and was known in Salem for her faith and good works. She was also known for publicly chastising her husband for his practice of visiting a tavern when in port instead of coming home to her and their family. She used her sharp tongue to tell a neighbor to mind his own business instead of gossiping about her. That she was outspoken in asserting her opinions would have given people reason to suspect diabolical connections. The trip from suspicion to accusation was very, very short in Salem.

In addition to the confusion over all the Mary Parkers in the area, it may also be that gossips referred, as was the common practice, to “Goody Parker” rather than the woman’s first name. After the gossip laden stories were passed along a number of times, some may have mistaken one Parker for another. While there is absolutely no evidence that Alice Parker and Mary Parker were related, mention of Goody Parker would have drawn attention to any woman with that last name. The very name would have aroused suspicion.

While not much is actually known about Alice Parker, there has been some speculation that Alice was the step-daughter of Giles Corey, the man who, after refusing to answer charges, was crushed with stones on his chest to force an answer from him. According to legend, “More weight” were his last words.

According to Reiss in Spellbound, “The Alice Parker who was executed in 1692 may or may not have been Giles Corey’s daughter. Both a Mary Parker of Andover and an Alice Parker, wife of John Parker, of Salem, were hanged as witches that year. Giles (and his former wife Mary) had a daughter who was married to John Parker of Salem, but her name was usually given as Mary. Names like Mary and Alice were sometimes used interchangeably in early New England, and I suspect that the Alice Parker who was executed was in fact Giles Corey’s daughter.”

If Reiss is correct in her supposition, Alice not only died with another Parker, she died with her stepmother, Martha Corey.

Additional Biographical Sources

Baker, E. , W. (2015). A Storm of Witchcraft. Pivotal Moments in American Hi.

Hite, R. (2018). In the Shadow of Salem.

John. (2018, August 15). Mary Ayer Parker-12th Great Aunt. My Family History Research. Retrieved May 20, 2019, from https://repinskifamily.blogspot.com/2018/08/mary-ayer-parker-11th-great-aunt.html

Mary Ayer Parker (mid-1600’s-1692. Legends of America: Witches of Massachusetts. (2003). Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ma-witches-c/3/

Mary Ayer Parker. History of American Women: Colonial Women. Retrieved March 4, 2019, from http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/06/mary-ayer-parker.html

Reis, E. (2004). Spellbound: women and witchcraft in America. Lanham, MD: SR Books.

Primary Source on Parker’s Examination, Indictments, Accusers

Best available location:

“SWP No. 098: Mary Parker Executed, September 22, 1692.” SWP No. 098: Mary Parker Executed, September 22, 1692 – New Salem – Pelican, University of Virginia, 2018, salem.lib.virginia.edu/n98.html.